Difference between revisions of "Template:Marker:Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition"

(Created page with "Image:RG2752-PH000001-000001_SFN102231_1w.jpg|thumb|center|upright=3.0|alt=RG2752-PH000001-000001_SFN102231_1w.jpg|The Grand Court at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition. (''Ne...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | ==Further Information== | ||

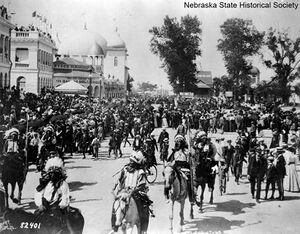

[[Image:RG2752-PH000001-000001_SFN102231_1w.jpg|thumb|center|upright=3.0|alt=RG2752-PH000001-000001_SFN102231_1w.jpg|The Grand Court at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition. (''Nebraska State Historical Society'')]] | [[Image:RG2752-PH000001-000001_SFN102231_1w.jpg|thumb|center|upright=3.0|alt=RG2752-PH000001-000001_SFN102231_1w.jpg|The Grand Court at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition. (''Nebraska State Historical Society'')]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:41, 21 March 2017

Further Information

In 1898, Omaha hosted the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, generally known as the Trans-Mississippi Expo. This World’s Fair was meant to exhibit the wonders of the West and boost the economy of Omaha.

World’s Fairs

World’s Fairs captured the public’s imagination during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They were intended to display a society’s achievements and successes while envisioning a bold path for the future. The first World’s Fair was held in London in 1851. Other notable World’s Fairs took place in Philadelphia in 1876 and Paris in 1889.

The Columbian Exposition

In 1893, on the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage to America, a World’s Fair was held in Chicago. It was somewhat surprising that a larger eastern city was not chosen; Chicago was still a growing city at the time. Since a more western location was chosen, the fair focused on the achievements of the West. Frederick Jackson Turner presented his famous Frontier Thesis at the exposition, saying that the western frontier was the defining aspect of America’s history, but that it was now gone with the occupation of the West. Despite its western slant, some westerners still felt that the Columbian Exposition was too focused on eastern achievements, and that a special western fair should be held to exhibit western achievements.

The Trans-Mississippi Commercial Congress

In 1894, a meeting was held in St. Louis to discuss the possibility of a distinctly western World’s Fair. The meeting of what became known as the Trans-Mississippi Commercial Congress made no major decisions except to meet in Omaha the following year. In 1895, William Jennings Bryan gave a speech to the congress, outlining the western ideals the exposition should entail. He proposed that they ask Congress to hold a World’s Fair in Omaha in 1898. His proposal was unanimously adopted.

Preparing for the Expo

In 1896, the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition Association was created. Gurdon Wattles, a prominent Omaha banker, was named the president of the association, with Herman Kountze vice president and John Wakefield as secretary. Wattles had only recently moved to Omaha, in 1892, but had become very involved in civic life there. Nebraska Senator William V. Allen introduced a bill in Congress for the appropriation of funds for the expo. The bill was opposed in the House by a Nebraska representative named Omar Kem, who tried to block all bills in the House after the Speaker of the House had failed to recognize him for introducing a bill concerning the disposal of the Fort Sidney Military Reservation. Kem was hanged in effigy in Benson, and many Nebraskans wrote to him in opposition. The bill passed Congress regardless.

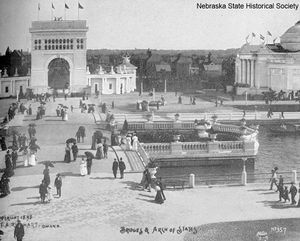

The exposition also found opposition in the state legislature. Many non-urban Nebraskans felt that the exposition would only help Omaha, and therefore would be a waste of state funds. Funding for the exposition came from the legislature anyway. Several neighboring states also contributed funds. Promotion and publicity became a major part of the preparations. A committee of women was created to help promote the expo, but most of the work went to newspapers. Gilbert Hitchcock of the Omaha World-Herald was originally the publicity chair, but he withdrew and was replaced with the editor of his rival paper, Edward Rosewater of the Omaha Bee, leading to a war of words between the newspapers regarding the expo’s publicity. Five different locations around the city were considered for the location of the expo. Eventually a site in North Omaha, between 24th Street and Sherman Avenue south of Ames, was chosen. (Modern-day Kountze Park is located where the Grand Court used to be.)

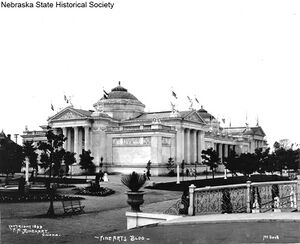

The Grand Court consisted of a lagoon surrounded by buildings. The main building was the Government building, at the head of the lagoon. Other buildings in the Grand Court included exhibits of fine arts, liberal arts and mining to the south and agriculture, manufacturing, machinery and electric to the north. Most of the buildings were designed by Thomas R. Kimball and C. Howard Walker, the architects-in-chief. They were all white with grey roofs and were based on Renaissance architecture. All the buildings were made with wood and plaster since they were intended to be temporary buildings.

Problems

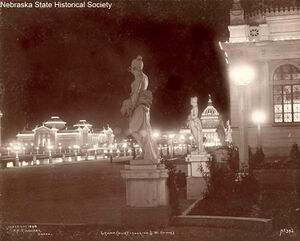

Dion Geraldine, the superintendant of construction, was involved in some corrupt activities involving the construction of the expo. He resigned in 1897, but his actions cost the expo tens of thousands of dollars. Shortly before the Expo opened, the Spanish-American War began. The war both helped and hurt the expo: it took away some of the publicity for the expo, but also convinced some people to stay in the country for entertainment rather than vacation abroad. Just over one week before the expo started, two members of the Salvation Army sneaked into the Grand court and defaced two nude statues they felt were immodest. They were both arrested and fined.

The Expo

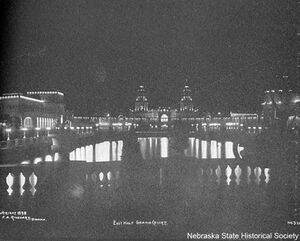

Despite the Spanish-American War, attendance was high at the opening of the Expo. About 6,000 people attended the Opening Day festivities on June 1, 1898. The Omaha expo was the first World’s Fair to open on schedule with most of its buildings complete. The festivities included a parade, music, and speeches from local leaders. Senator Allen sent a letter to the delegation, since he was involved in important war discussions in Congress. President McKinley was supposed to greet the expo by phone, but instead sent a telegram read by Governor Silas Holcomb. At 1:30, McKinley pushed a button in the White House connected to Omaha that turned on the lights of the Grand Court. Governor Holcomb concluded the events with a speech.

Twenty-eight states and three territories contributed to the expo, thus making it a national rather than regional affair. Although 42 countries were invited to participate, only Mexico sent an official exhibit to the fair. France, Italy, Russia, Switzerland, Denmark, Austria, England, Germany, Canada and China were represented by private groups. Different days during the expo celebrated different places, groups or things. Special days included: Chicago Day, German Day, Military Day, Nebraska Peach Day, Colored People’s Day and Texas Watermelon Day. One of the main attractions of the expo was electricity. Electricity had been a major part of World’s Fairs since 1857. The Trans-Mississippi Expo was the first to feature lights all the way around its Grand Court. Henry Rustin, an Omaha electrician, suggested that lighting be incorporated into the buildings around the Grand Court. These plans were kept secret until the opening ceremonies, when President McKinley turned them on. By 1898, electricity was commonplace in cities, but for rural Nebraskans it was a wonder to behold.

Buffalo Bill Cody

One of the most famous Nebraskans and, indeed, one of the most famous Americans at the time was Buffalo Bill Cody, creator of the world-famous Wild West Show. Buffalo Bill’s first Wild West Show was performed in Omaha, and he performed at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was thus only natural that he perform at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha. August 31 was called “Cody Day,” and his performance became so popular it had to be moved to a bigger venue two miles south of the expo grounds.

The Indian Congress

In 1897, it was proposed that an Indian Congress be added to the Exposition’s festivities. Congress approved of the plan. Its purpose was to “represent the different Indian tribes and their primitive modes of living; to show their manner of dress, illustrate their superstitions; and to recall, as far as possible, their almost forgotten traditions.” The Indian Congress opened on August 4, 1898 with about 450 Indians, many of them coming from the Omaha and Winnebago tribes, in attendance. There were 23 tribes represented at the Congress. Perhaps the most famous attendee was Apache Chief Geronimo. F. A. Rinehart, the official photographer of the expo, took many celebrated pictures of attendees of the Indian Congress which have been noted for capturing the Indians’ beauty and humanity.

President’s Day

President William McKinley visited the expo on October 12 accompanied by some of his cabinet. His appearance drew huge crowds to Omaha. Total admissions at the expo that day were 98,845. The president was deeply grateful to the people of Omaha for their hospitality. The rest of the week was called “Peace Jubilee Week,” dedicated to the end of the Spanish-American War.

The End of the Expo

The Exposition’s last day was October 31, designated as “Omaha Day.” After a series of speeches from the mayor, Gurdon Wattles and others, the lights were turned off and the doors of the expo were closed. The total attendance for the exposition was 2,613,508. It had a total revenue of $1,977,338. Shareholders who had lent money to the exposition were given a 90% refund, considered a remarkable return on investment for a World’s Fair. The impact the expo had on Omaha’s economy, culture and future are not quantifiable, but it was easily one of the biggest events in the early city’s history. Since all the buildings were temporary, they were torn down after the exposition’s end. Today, there are no remaining signs of the exposition at the site, though a few artifacts of the expo can be found in the Joslyn Art Museum or other places around the city.

Bibliography

Alfers, Kenneth G. “Triumph of the West: The Trans-Mississippi Exposition.” Nebraska History. Fall 1972: 313-329.

“Calendar of Events.” Omaha Public Library. Web.

Johnson, Amanda N. “Illuminating the West: The Wonder of Electric Lighting at Omaha’s Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition of 1898.” Nebraska History. Winter 2012: 183-191.

“The Indian Congress of 1898.” Omaha Public Library. Web.